The Romans in Iberia

Hispania was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula.

Roman armies invaded Hispania in 218 BC and used it as a training ground for officers and as a proving ground for tactics during campaigns against the Carthaginians, the Iberians, the Lusitanians, the Gallaecians and other Celts. It was not until 19 BC that the Roman emperor Augustus (r. 27 BC-AD 14) was able to complete the conquest. Until then, much of Hispania remained autonomous.

Roman armies invaded Hispania in 218 BC and used it as a training ground for officers and as a proving ground for tactics during campaigns against the Carthaginians, the Iberians, the Lusitanians, the Gallaecians and other Celts. It was not until 19 BC that the Roman emperor Augustus (r. 27 BC-AD 14) was able to complete the conquest. Until then, much of Hispania remained autonomous.

Romanization proceeded quickly in some regions where we have references to the togati, and very slowly in others, after the time of Augustus, and Hispania was divided into three separately governed provinces (nine provinces by the 4th century). More importantly, Hispania was for 500 years part of a cosmopolitan world empire bound together by law, language, and the Roman road. But the impact of Hispania in the newcomers was also big. Caesar wrote on the Civil Wars that the soldiers from the Second Legion had become Hispanicized and regarded themselves as hispanicus.

Some of the peninsula's population were admitted into the Roman aristocratic class and they participated in governing Hispania and the Roman empire, although there was a native aristocracy class who ruled each local tribe. The latifundia (sing., latifundium), large estates controlled by the aristocracy, were superimposed on the existing Iberian landholding system.

The Romans improved existing cities, such as Lisbon (Olissipo) and Tarragona (Tarraco), established Zaragoza (Caesaraugusta), Mérida (Augusta Emerita), and Valencia (Valentia), and reduced other native cities to mere villages. The peninsula's economy expanded under Roman tutelage. Hispania served as a granary and a major source of metals for the Roman market, and its harbors exported gold, tin, silver, lead, wool, wheat, olive oil, wine, fish, and garum. Agricultural production increased with the introduction of irrigation projects, some of which remain in use today. The Romanized Iberian populations and the Iberian-born descendants of Roman soldiers and colonists had all achieved the status of full Roman citizenship by the end of the 1st century. The emperors Trajan (r. 98-117), Hadrian (r. 117-138), and Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180) were of Hispanic origin. The Iberian denarii, also called argentum oscense by Roman soldiers, circulated until the 1st century BC, after which it was replaced by Roman coins.

Hispania was separated into two provinces (in 197 BC), each ruled by a praetor: Hispania Citerior ("Hither Hispania") and Hispania Ulterior ("Farther Hispania"). The long wars of conquest lasted two centuries, and only by the time of Augustus did Rome managed to control Hispania Ulterior. Hispania was divided into three provinces in the 1st century BC.

In the 4th century, Latinius Pacatus Drepanius, a Gallic rhetorician, dedicated part of his work to the depiction of the geography, climate and inhabitants of the peninsula, writing:

This Hispania produces tough soldiers, very skilled captains, prolific speakers, luminous bards. It is a mother of judges and princes; it has given Trajan, Hadrian, and Theodosius to the Empire.

With time, the name Hispania was used to describe the collective names of the Iberian Peninsula kingdoms of the Middle Ages, which came to designate all of the Iberian Peninsula plus the Balearic Islands.

The Hispaniae

During the first stages of Romanization, the peninsula was divided in two by the Romans for administrative purposes. The closest one to Rome was called Citerior and the more remote one Ulterior. The frontier between both was a sinuous line which ran from Cartago Nova (now Cartagena) to the Cantabrian Sea.

Hispania Ulterior comprised what are now Andalusia, Portugal, Extremadura, León, a great portion of the former Castilla la Vieja, Galicia, Asturias, and the Basque Country.

Hispania Citerior comprised the eastern part of former Castilla la Vieja, and what are now Aragon, Valencia, Catalonia, and a major part of former Castilla la Nueva.

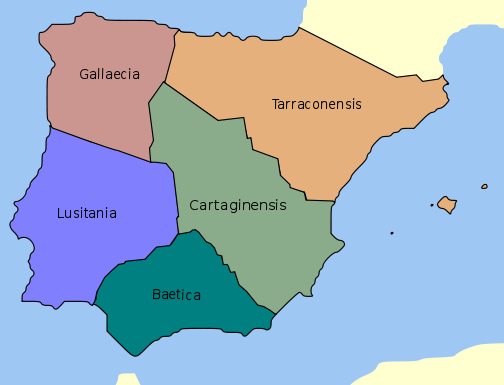

In 27 BC, the general and politician Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa divided Hispania into three parts, namely dividing Hispania Ulterior into Baetica (basically Andalusia) and Lusitania (including Gallaecia and Asturias) and attaching Cantabria and the Basque Country to Hispania Citerior.

The emperor Augustus in that same year returned to make a new division leaving the provinces as follows:

- Provincia Hispania Ulterior Baetica (Hispania Baetica), whose capital was Corduba, presently Córdoba. It included a little less territory than present-day Andalusia - since modern Almería and a great portion of what today is Granada and Jaén were left outside - plus the southern zone of present-day Badajoz. The river Anas or Annas (Guadiana, from Wadi-Anas) separated Hispania Baetica from Lusitania.

- Provincia Hispania Ulterior Lusitania, whose capital was Emerita Augusta (now Mérida) and without Gallaecia and Asturias.

- Provincia Hispania Citerior, whose capital was Tarraco (Tarragona). After gaining maximum importance this province was simply known as Tarraconensis and it comprised Gallaecia (modern Galicia and northern Portugal) and Asturias. In AD 69, the province of Mauretania Tingitana was incorporated into the Diocesis Hispaniarum.

By the 3rd century the emperor Caracalla made a new division which lasted only a short time. He split Hispania Citerior again into two parts, creating the new provinces Provincia Hispania Nova Citerior and Asturiae-Calleciae. In the year 238 the unified province Tarraconensis or Hispania Citerior was re-established.

In the 3rd century, under the Soldier Emperors, Hispania Nova (the northwestern corner of Spain) was split off from Tarraconensis, as a small province but the home of the only permanent legion is Hispania, Legio VII Gemina. Beginning with Diocletian's Tetrarchy reform in AD 293, the new dioecesis Hispaniae became one of the four dioceses - governed by a vicarius - of the praetorian prefecture of Gaul (also comprising the provinces of Gaul, Germania and Britannia), after the abolition of the imperial Tetrarchs under the Western Emperor (in Rome itself, later Ravenna). The diocese, with capital at Emerita Augusta (modern Mérida), comprised the five peninsular Iberian provinces (Baetica, Gallaecia and Lusitania, each under a governor styled consularis; and Carthaginiensis, Tarraconensis, each under a praeses), the Insulae Baleares and the North African province of Mauretania Tingitana.

In the 3rd century, under the Soldier Emperors, Hispania Nova (the northwestern corner of Spain) was split off from Tarraconensis, as a small province but the home of the only permanent legion is Hispania, Legio VII Gemina. Beginning with Diocletian's Tetrarchy reform in AD 293, the new dioecesis Hispaniae became one of the four dioceses - governed by a vicarius - of the praetorian prefecture of Gaul (also comprising the provinces of Gaul, Germania and Britannia), after the abolition of the imperial Tetrarchs under the Western Emperor (in Rome itself, later Ravenna). The diocese, with capital at Emerita Augusta (modern Mérida), comprised the five peninsular Iberian provinces (Baetica, Gallaecia and Lusitania, each under a governor styled consularis; and Carthaginiensis, Tarraconensis, each under a praeses), the Insulae Baleares and the North African province of Mauretania Tingitana.

Christianity was introduced into Hispania in the 1st century and it became popular in the cities in the 2nd century. Little headway was made in the countryside, however, until the late 4th century, by which time Christianity was the official religion of the Roman Empire. Some heretical sects emerged in Hispania, most notably Priscillianism, but overall the local bishops remained subordinate to the Pope. Bishops who had official civil as well as ecclesiastical status in the late empire continued to exercise their authority to maintain order when civil governments broke down there in the 5th century. The Council of Bishops became an important instrument of stability during the ascendancy of the Visigoths.

Rome continued to dominate the area until the collapse of the Empire in the west. Four tribes of invaders arrived in 409 and caused much trouble. Two of them, the Alans and Siling Vandals were virtually wiped out in 418 by the Visigoths at the order of the Romans. After the departure of the Vandals in 429 only the Sueves remained in a northwest corner of the peninsula. Roman rule which had survived in the eastern quadrant was restored over most of Iberia for 10 years. The diocese may even have been re-established with the capital at Mérida in 418. If so it ended when the Sueves took the city in 439. The Visigoths, a Germanic people, whose kingdom was in southwest Gaul, took the last Roman province when they occupied Tarragona, the capital, in 472. They also confined the Sueves to Galicia and northern Portugal.